Uncounted

Often, when I talk about homelessness, my brother comes up. In his 20s he developed paranoid schizophrenia. He struggled to maintain a job, and housing, and spent time homeless during his 20s and 30s. When he started receiving his meager social security check, he was able to secure a two-room efficiency unit in Olympia that included a sink, with a bathroom down the hall. At $400/mo it was more than 30% of his monthly income, but it was safe, and warm, and it kept him off the street. This was private housing - no public subsidy, no voucher, no case manager - and that small and inexpensive space was the only thing that kept him from sleeping on the street. I will forever be thankful for his landlord for keeping my brother’s rent low and keeping him safe.

For most of my life, and I know that I am not alone in this, the concept that I had of what “homeless” meant was confined to the type of homelessness my brother had experienced sleeping on the streets or in a shelter. What I’ve come to understand is that this literal, or visual, homelessness makes up just a small piece of the total picture. Nearly three years ago, a friend was wrongfully evicted from his apartment, and without anywhere else to go, he stayed with us for the next two years. Self-employed with a good job, he made money but the 3x rent-to-income ratio, credit score requirements, and high rent made it impossible for him to find a place of his own. With a stable job and a roof over his head, he didn’t fit my understanding of “homeless” and didn’t fit the definition needed for assistance, or to be counted in the “point in time” count, either.

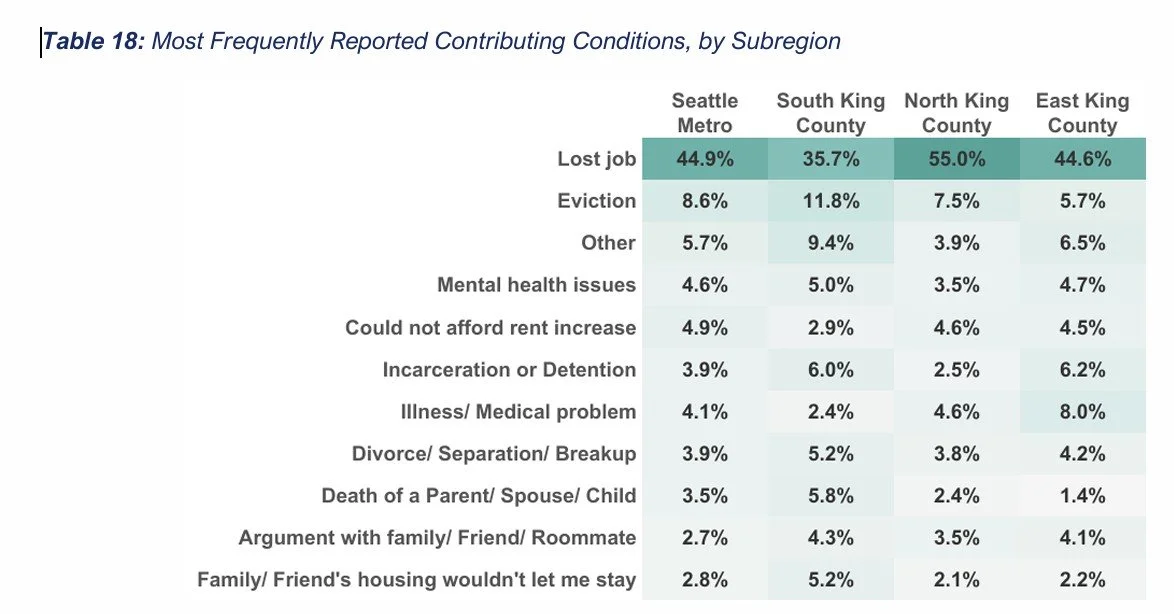

Working closely with renters and homeowners and have seen the sacrifices that people are willing to make for the sake of having a roof over their heads - overcrowded roommate situations, financial overextension, obscenely long commutes, and more. When you take 50% of pre-tax income for a dual-income household and dedicate it to mortgage, what happens in the event of a job loss? Disability? Extended illness? Housing is so expensive, and the calculation so delicate, that any minor disruption in the system can break it. Our shortage of homes, and the high (and rising) costs have worked together to create a crisis of homelessness that cannot be solved by shelters and permanent-supportive housing, or by addiction and mental health treatment. In the 2024 King County Point in Time Count, well over half of people experiencing homelessness said it was due to a job loss, where less than 11% cited substance abuse, mental health and criminal history combined.

Although he was experiencing homelessness at the time, the friend we had staying with us would not have been included in the “point in time” count. In There Is No Place for Us, Brian Goldstone tells an, emotional, data-rich, story of five working families in Atlanta struggling to maintain housing. In the epilogue, Goldstone notes that because the “point in time” counts have been designed to only capture people living on the streets or staying in shelters. As a result, none of the five families that he followed in the book would have been included - staying in their car, with a friend, or at an extended stay motel on the night of the count they were all experiencing homelessness, but they nonetheless would have been uncounted.

The statics on how much we are undercounting are staggering. Goldstone cites Georgia numbers - a “point in time” count of just over 10k, while over 106k school children are living in a hotel, and approximately 118k residents were “doubled up” (staying with friends/family). His estimate of the true number of people nationwide experiencing homelessness is over four million.

In Homelessness is a Housing Problem, Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page Aldern take a data-heavy look at what is driving such high rates of homelessness, analyzing the variations and looking for the factors that cause rates to be higher in some cities than others. What they find is that the wealthiest regions often have the highest rates of homelessness because the root of the problem is high housing cost, low supply and low elasticity (ability to respond to changing needs quickly). In a high cost/low supply market, renters with lower or inconsistent incomes, or imperfect credit, will often lose out on homes the apply to rent. Unable to find less expensive options, or a quick place in the event of a sudden financial change (job loss, rent increase) they are easily pushed out of housing altogether.

At the last STEP Housing meeting we spoke with a panel of experts. Two things that they said stuck with me - the first was one who said that in his estimate we are twelve years away from peak homelessness in Washington. The second is that our fastest growing demographic of people experiencing homelessness is seniors. Seniors on a fixed income are most vulnerable, because Social Security is below market rent in most areas. Even if you are currently in a place you can afford, a small rent increase can change that calculation. At Kenmore’s Heron Haven, seniors are priced out by $200-300 per month.

Understanding the cause and the changing face of homelessness is vital towards making any steps to change it. We need to not only ensure that we are providing adequate services to people who are currently experiencing homelessness, but we also need to work diligently at changing the structural causes that continue to push more people out of safe, secure and affordable housing and into homelessness. Treating the symptom without addressing the cause means that we never find a solution, and with clear evidence of what the cause is, we need to work harder than ever on a solution.